As we enter 2026, the SEND system in England is under unprecedented strain. Identification rates continue to rise, statutory processes are overwhelmed, and schools are struggling to meet need within finite budgets and capacity. The dominant narrative is one of complexity: complex pupils, complex needs, complex systems. But this framing risks obscuring a more uncomfortable truth.

Many pupils now described as “complex” are not inherently so. They are responding, often predictably, to unmet wellbeing, relational and environmental needs that have gone unidentified for too long.

When Unmet Need Becomes “Complexity”

Over the past decade, the number of children receiving SEN support or Education, Health and Care Plans has increased sharply. Parliamentary inquiries and sector reports consistently point to a system that is reactive rather than preventative, escalating need into statutory pathways because earlier support was unavailable, inconsistent or invisible.

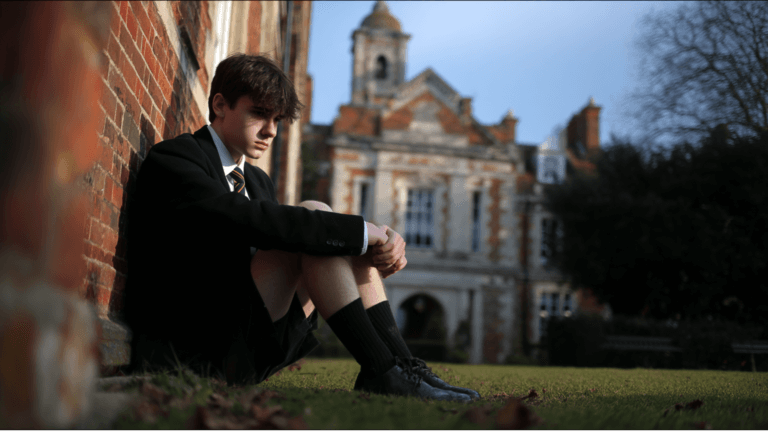

What often begins as low-level vulnerability – poor emotional regulation, low self-belief, disrupted relationships, anxiety, unmet health needs – can harden into entrenched difficulty when left unaddressed. Behaviour escalates. Attendance falters. Learning disengages. Only then does the system respond, frequently through diagnostic labels and formal plans.

In this context, “complexity” is not a starting point. It is an outcome.

The Predictable Pathway to SEND

Evidence increasingly suggests that many SEND referrals sit at the end of a familiar pathway:

- Early emotional or relational vulnerability

- Reduced engagement and confidence

- Behavioural or attendance concerns

- Escalation into SEND identification

Crucially, this pathway is often data-poor. Schools are highly attuned to academic performance and behaviour incidents, but far less equipped to systematically identify wellbeing, self-efficacy and relational breakdown before they manifest as crisis.

As a result, support arrives late, thresholds rise, and pupils become labelled as “hard to support” when the reality is that the system struggled to see their needs early enough.

Why Wellbeing and Self-Efficacy Change the Conversation

Wellbeing and self-efficacy data offer a fundamentally different lens.

Self-efficacy – a pupil’s belief in their ability to succeed – is one of the strongest predictors of engagement, persistence and resilience. When belief erodes, effort follows. Low self-efficacy often precedes disengagement, avoidance and behavioural difficulty, yet it rarely appears in traditional school data.

Similarly, wellbeing indicators such as sleep, emotional regulation, physical activity and sense of belonging strongly influence a pupil’s capacity to learn and self-manage. When these domains are compromised, learning difficulties are often misinterpreted as ability gaps or behavioural deficits.

When schools can see these factors clearly, conversations shift:

- from “What’s wrong with this child?”

- to “What needs are going unmet?”

This reframing is not about lowering expectations. It is about targeting support proportionately and early, before need escalates into formal SEND pathways.

The Cost of Late Intervention

Late identification carries a human and systemic cost.

For pupils, it can mean years of frustration, failure and diminished self-worth before help arrives. For families, it often means adversarial processes and prolonged uncertainty. For schools and local authorities, it drives unsustainable pressure on specialist services and statutory provision.

Parliamentary evidence is clear: early identification and proportionate support reduce long-term demand. Yet early help only works if schools have the tools and confidence to identify need before it becomes visible through failure.

From Individual Labels to System Design

One of the most persistent myths in SEND discourse is that rising demand reflects a sudden increase in inherently complex children. A more plausible explanation is that systems have become less able to absorb vulnerability early.

Inclusive education is not achieved through individual plans alone. It is achieved through:

- strong relational practice

- consistent adult support

- environments that build confidence and belonging

- insight that allows schools to intervene early and precisely

When these conditions are in place, fewer pupils require escalation. Complexity reduces because need is addressed upstream.

The Role of Insight and Mentoring

This is where approaches grounded in relationship quality and early insight become critical.

Mentoring, when delivered consistently and relationally, provides pupils with a trusted adult who can surface concerns long before they appear in behaviour logs or attendance data. It strengthens self-efficacy, supports emotional regulation and restores a sense of agency.

At the same time, structured insight – particularly pupil voice and wellbeing data — enables schools to identify patterns that would otherwise remain hidden. Rather than relying on instinct or crisis response, schools can target support where vulnerability is emerging and track whether interventions are working.

The Evolve Development Tracker (EDT) supports this shift by giving schools visibility of wellbeing, self-belief and relational experience alongside more familiar indicators. This does not replace professional judgement; it strengthens it. By making early vulnerability visible, EDT helps schools intervene proportionately, refine support and reduce unnecessary escalation.

Rethinking “Complex”

As the SEND system continues to strain under demand, the sector faces a choice. We can continue to label children as increasingly complex – or we can acknowledge that complexity often reflects late recognition, fragmented support and invisible need.

Reframing SEND through a wellbeing and self-efficacy lens does not diminish the reality of profound and lifelong needs. But it does challenge the assumption that escalation is inevitable.

Many pupils do not need more labels. They need earlier understanding, stronger relationships and systems designed to see them before they struggle.

If we want a sustainable SEND system, the answer lies not only in reforming statutory processes, but in redesigning how schools identify and respond to vulnerability in the first place. When wellbeing is prioritised early, complexity often reduces – and more children are supported to thrive within inclusive, mainstream settings.